From Tap to Packet: Exploring Card Payments on Interledger

Written by Jason BruwerCard payments are the backbone of global commerce-trusted, regulated, and deeply entrenched. Our latest exploration asks a pivotal question: how can we bring the ubiquity of card payments into the Interledger ecosystem without compromising the security and standards of the EMV model (standard EMV flow/state machine for an ICC/contactless transaction)?

Rafiki is an open-source platform that enables Account Servicing Entities (ASEs) like banks and digital wallet providers to integrate Interledger Protocol (ILP) functionality into their systems.

Table of Contents

- Card Payments Using Rafiki and ILP

- Exploring a Path from EMV Cards to Interledger

- Starting Point: Should you build a Kernel

- ‘Hello World’ for POS (Point of Sale): How Does a POS device become “Known”?

- The Transaction Moment

- Conclusion, Where This Leaves Us

- What is next for ILF and Cards?

- References

- Glossary of Terms

Card Payments Using Rafiki and ILP

At a high level, an ILP card transaction involves:

- Card (ICC) - EMV-compliant card with an Open Payments enabled wallet address

- POS Device - EMV kernel + ILP extensions

- Merchant ASE - Runs Rafiki and manages POS trust (RKI, IPEK lifecycle, compliance)

- Customer ASE - Runs Rafiki and manages the cardholder account

- Interledger Network - Routes value between ASEs

Exploring a Path from EMV Cards to Interledger

Card payments are everywhere. They are trusted, heavily regulated, and backed by decades of operational experience. At the same time, they are often locked into closed networks and bespoke integrations.

What we have been exploring is a simple question: What if card payments could naturally flow into Interledger without breaking EMV, without replacing kernels, and without weakening the security model everyone already relies on? This post is a walkthrough of that exploration - not a final specification, but a journey through the design decisions, trade-offs, and the emerging shape of an ILP-enabled card flow built around Rafiki, existing EMV kernels, and a small set of new supporting services.

Starting Point: Should you build a Kernel?

In the world of card payments, a kernel is the core software component within a POS terminal that manages the complex interaction between the payment card (the chip) and the terminal. It handles the EMV protocol logic, data-exchange, and cryptographic processing required to authorize a transaction. Essentially, it is the “brain” that knows how to speak “chip card” securely and according to global standards.

With the kernel being the “brain” of the POS, it quickly became clear that our first major design decision would revolve around which kernel approach to build on. The earliest and most important decisions came out of conversations with our first POS (Point of Sale) manufacturing partner, who provides both the EMV kernel and a significant portion of the overall payment software stack running on the device. Because ILF’s first objective is to enable SoftPOS, we needed to choose between two approaches:

- developing a completely new EMV kernel based on the latest EMVCo C8 specifications,

- or leveraging the existing certified kernel already embedded in the payment stack (C2).

After evaluating the options, it became clear that reusing the existing kernel was the most practical and lowest-risk path to delivering SoftPOS quickly and reliably.

The C8 certification path would have meant

- Brand new certification cycles

- Repeated scheme testing (Visa/Mastercard/etc.)

- Long iteration loops with labs

- Reviewing of the hardware and software stack

The C2 path means

- Existing correct EMV processing

- Secure PIN entry / PAN handling out-of-the box

- Already scheme compliant

Exploring was very clear:

- Use the C2 kernel

- Stay as close as possible to EMVCo documentation

- Avoid clever reinterpretations of kernel behavior

C2, while perhaps less feature-rich than newer kernels, is predictable, explicit, and specification-aligned. That predictability turned out to be far more valuable than flexibility.

The immediate consequence of this choice was important: ILF does not need to develop an EMV kernel.

Instead of re-implementing deeply complex, certification-heavy logic, we could focus on:

- APIs

- Cryptographic boundaries

- ILP and Open Payments integration

- Device onboarding

- Merchant management

- Remote key injection (RKI) and key rotation

That framing shaped everything that followed.

‘Hello World’ for POS (Point of Sale): How Does a POS device become “Known”?

Before a POS can send payments into Interledger, it needs an identity. Not only a “vague” merchant identity, but a cryptographically verifiable device identity. This led us to the first building block: POS onboarding.

POS Onboarding as a Trust Ceremony

Rather than treating onboarding as a provisioning script, we started thinking of it as a ceremony:

- The POS proves who it is (serial number, model)

- The ASE decides whether to trust it

- Cryptographic material is issued with clear ownership

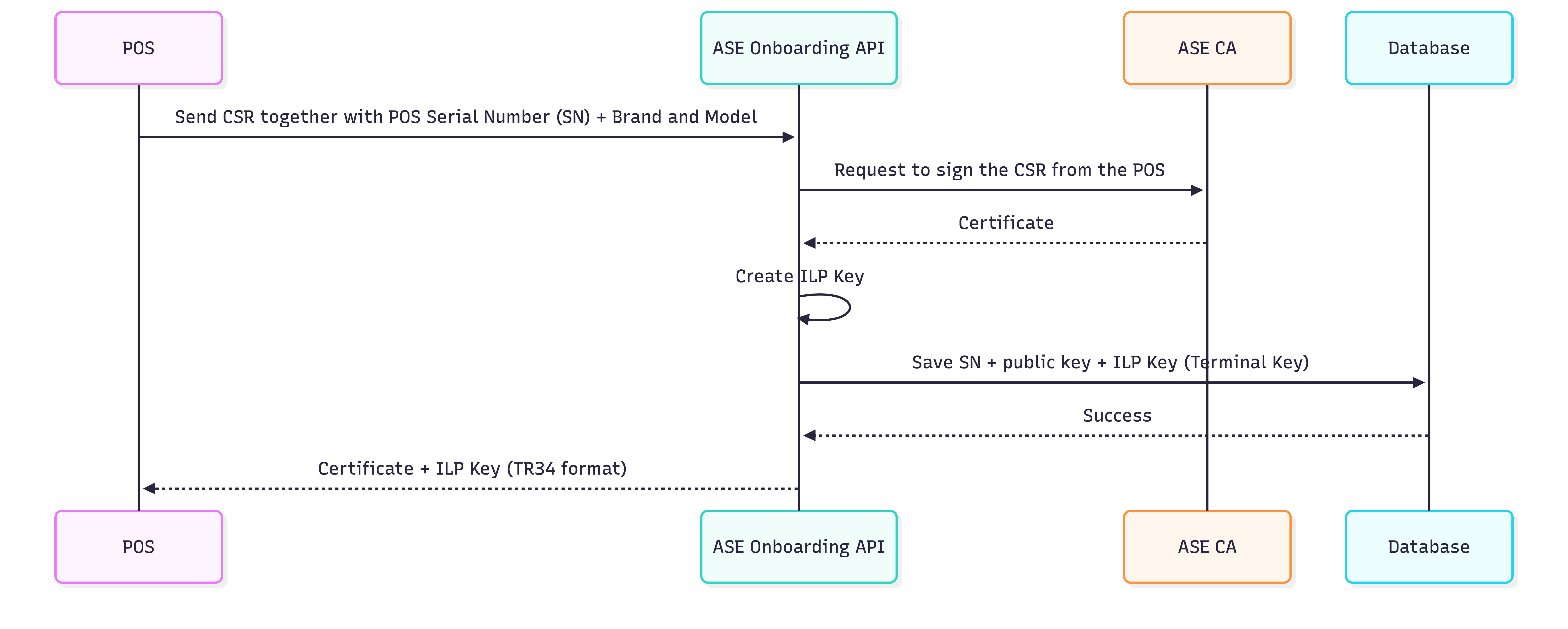

Onboarding

The rough onboarding flow regarding keys looks like this:

- The POS generates a key pair locally and sends a CSR, along with device metadata, to the ASE

- The ASE signs the CSR via its CA

- The ASE generates the IPEK (Initial PIN Encryption Key) for SRED/PIN (Secure Reading and Exchange of Data / Personal Identification Number)

- The ASE updates the terminal information to its database

- The ASE returns the signed certificate and IPEKs (TR-34) to the POS

- All keys are returned securely to the POS for storage

From this point on:

- The POS can authenticate itself

- The ASE can verify which device is speaking

- Every future request can be cryptographically tied back to onboarding

This turned out to be a crucial foundation, not just for transactions, but for everything else.

Then Reality Kicks In: Keys Don’t Live Forever

Once we started thinking seriously about certification (for example, MPOC), a practical requirement surfaced very quickly: Encryption keys must be rotated regularly (at least monthly)! This is where things get interesting.

The POS is already running:

- POS Manufacturer bespoke software (Android / Symbian / iOS / Windows Phone)

- POS kernel

- POS WhiteBox (secure software-based storage and execution environment for a POS device)

And the POS Manufacturer already has strong opinions (for good reasons) about:

- Where transaction keys live

- How PIN and PAN encryption happens

- What software is allowed to see those keys

So rather than fighting that model, we leaned into it. A Crucial Piece Emerges: Remote Key Injection (RKI) and Key Rotation! Instead of pushing key management into the kernel or POS logic, we introduced a new ASE-side service whose sole responsibility is key lifecycle management. Not payment processing. Not EMV logic. Just keys.

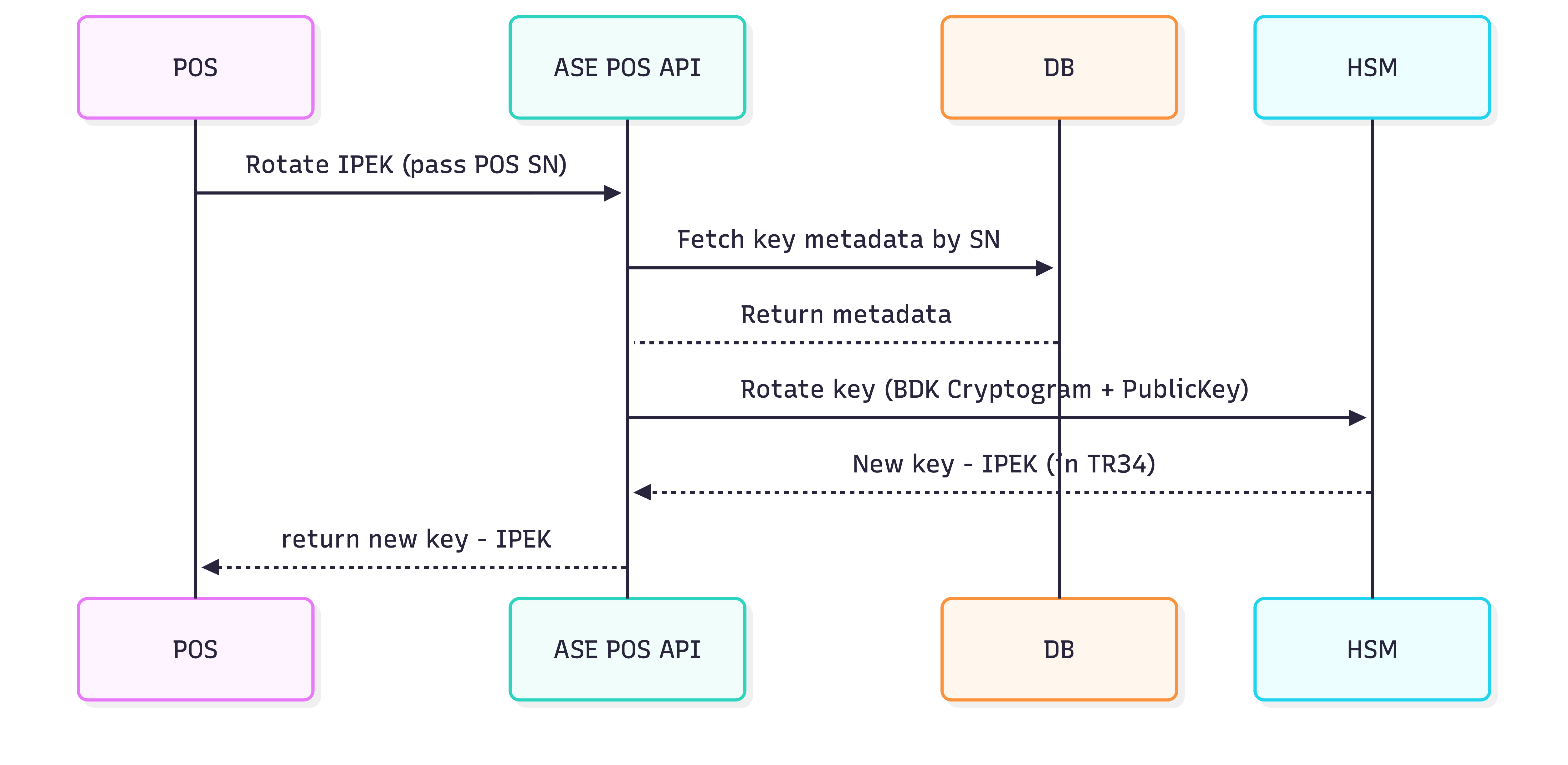

Key Rotation as a First-Class Flow

The key rotation (IPEK) flow looks like this:

- The POS requests a new set of IPEK keys from the ASE (via the POS API)

- The POS is cryptographically verified to ensure the request can be trusted

- A new IPEK is generated and stored at the ASE

- The new keys are securely returned to the POS (TR-34)

- The POS replaces the old keys in its secure storage with the new ones

In this model:

- The POS periodically asks the ASE for a new key

- The request is authenticated using the POS identity established during onboarding

- The ASE derives a new IPEK inside an HSM

- The key is wrapped (TR-34) and sent back

- POS Manufacturer stores it inside the POS secure WhiteBox

A subtle but important decision here:

- POS TMK (Terminal Master Key) is generated and injected during POS manufacturing

- Transaction keys live inside the WhiteBox

- Network / ILP keys live outside the POS SDK, in the device keystore

This clean separation keeps:

- Payment cryptography in the kernels domain

- ILP signing firmly under ASE control

At this point, the architecture started to feel “right”.

Cards Enter the Picture

With POS EMV kernel, onboarding and key rotation in place, cards themselves become almost… boring. And that is a good thing!

Card personalization follows standard EMV practice:

- Card keys are generated by the issuer (Customer ASE)

- A wallet address is bound to the card

- The private key lives securely on the chip

From an ILP perspective, the card is simply:

- A secure signing device

- A holder of a wallet address

- A producer of cryptographic proof during transactions

No special casing. No new assumptions.

The Transaction Moment

When a card is presented, everything up to this point has been preparation.

Now the familiar EMV flow kicks in:

SELECT AIDGET PROCESSING OPTIONSREAD RECORDGENERATE ACOptional PIN verification (Online)All sensitive operations happen:

- Inside the kernel

- Using session keys derived from the current IPEK

- With data protected by the WhiteBox

NB: Nothing ILP-specific leaks into this phase, by design.

Crossing the Boundary: From EMV to ILP

Once the kernel has done its job, the POS shifts context. Now it is no longer “doing EMV”, it is requesting a payment. This is where the ILP terminal key issued during onboarding finally comes into play.

The POS:

- Assembles transaction data

- References the cards wallet address (Customer ASE)

- Signs the request with its ILP key (Merchant ASE)

- Sends it to the Customer and Merchant ASE

Importantly, we don’t have the POS talk to Rafiki directly to authorize the transaction. Instead, we route everything through an ASE POS API:

Why?

- Authentication

- Policy enforcement

- Request normalization

- Future flexibility

- Certifications

- Key management

The ASE remains firmly in control. Rafiki does what it already does well. From here on, Rafiki is on familiar ground.

It:

- Creates incoming and outgoing payments (as well as processing the ILP payments)

- Applies Open Payments semantics

- Tracks lifecycle state

- Emits events

The POS eventually gets a simple answer:

Approved,DeclinedorFailed.

All the complexity stays on the backend, where it belongs.

What We Learned Along the Way

A few themes kept repeating during this exploration:

- Do not fight EMV, work with it

- Do not overload the kernel, extend around it

- Keys define trust boundaries more than APIs do

- Small, focused services are easier to reason about than monoliths

- Interledger fits best when it is complementary, not dominant

Conclusion, Where This Leaves Us

What is emerging is not a replacement for card payments, but an extension of them.

- Cards remain cards.

- Kernels remain kernels.

- ASEs remain accountable entities.

Interledger simply becomes the connective tissue that lets value move beyond traditional rails, securely, incrementally, and without forcing the ecosystem to start over.

What is next for ILF and Cards?

- Further development of the Card applet for

C2kernel support - Further development of the Rafiki APIs to support the new POS/Card services

- New Merchant-API service to support ASEs with regards to:

- Merchant onboarding

- Terminal configuration and onboarding

- Merchant management

- Remote key injection (RKI)

References

- ADPU: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Smart_card_application_protocol_data_unit

- EMV C2 Specification: https://www.emvco.com/specifications/?search_bar_keywords=c-2

- EMV C8 Specification: https://www.emvco.com/specifications/?search_bar_keywords=c-8

- EMV C8 Specification: https://www.emvco.com/specifications/?search_bar_keywords=c-8

Glossary of Terms

| Term | Description |

|---|---|

AC | Application Cryptogram (generated during EMV processing, e.g., via “GENERATE AC”) |

ADPU / APDU | Application Protocol Data Unit (smart card command/response format; commonly spelled APDU) |

AID | Application Identifier (identifies an EMV application on a card; used in “SELECT AID”) |

API | Application Programming Interface |

ASE | Account Servicing Entity (e.g., a bank or wallet provider running/operating accounts and services) |

CA | Certificate Authority (signs certificates/CSRs) |

CI | Continuous Integration (automated build/test pipeline) |

CSR | Certificate Signing Request |

C2 / C8 | EMVCo kernel/specification “level” referenced in the article (e.g., choosing an existing certified kernel vs. a newer certification path). These refer specifically to EMV Contactless Kernel specifications. |

EMV | Card payment standard originally from Europay, Mastercard, Visa |

EMVCo | The organization that maintains and publishes EMV specifications (EMV Cooperation) |

HMAC | Hash-based Message Authentication Code |

HSM | Hardware Security Module (secure key generation/storage/crypto operations) |

ICC | Integrated Circuit Card (chip card; in EMV contexts, the card itself) |

ILP | Interledger Protocol |

IPEK | Initial PIN Encryption Key |

JSON | JavaScript Object Notation |

MPOC | Mobile Payments on COTS (COTS = Commercial Off-The-Shelf; a payments/security certification context) |

PAN | Primary Account Number (card number) |

PIN | Personal Identification Number |

POS | Point of Sale |

RKI | Remote Key Injection |

SDK | Software Development Kit |

SoftPOS | Software Point of Sale (POS implemented primarily in software) |

SRED | Secure Reading and Exchange of Data |

TMK | Terminal Master Key |

TR-34 | ANSI TR-34 key exchange / key block standard used for secure key distribution (often referenced in payments key injection) |

URL | Uniform Resource Locator |

As we are open source, you can easily check our work on GitHub. If the work mentioned here inspired you, we welcome your contributions. You can join our community slack or participate in the next community call, which takes place each second Wednesday of the month.

If you want to stay updated with all open opportunities and news from the Interledger Foundation, you can subscribe to our newsletter.